In search of Doñana

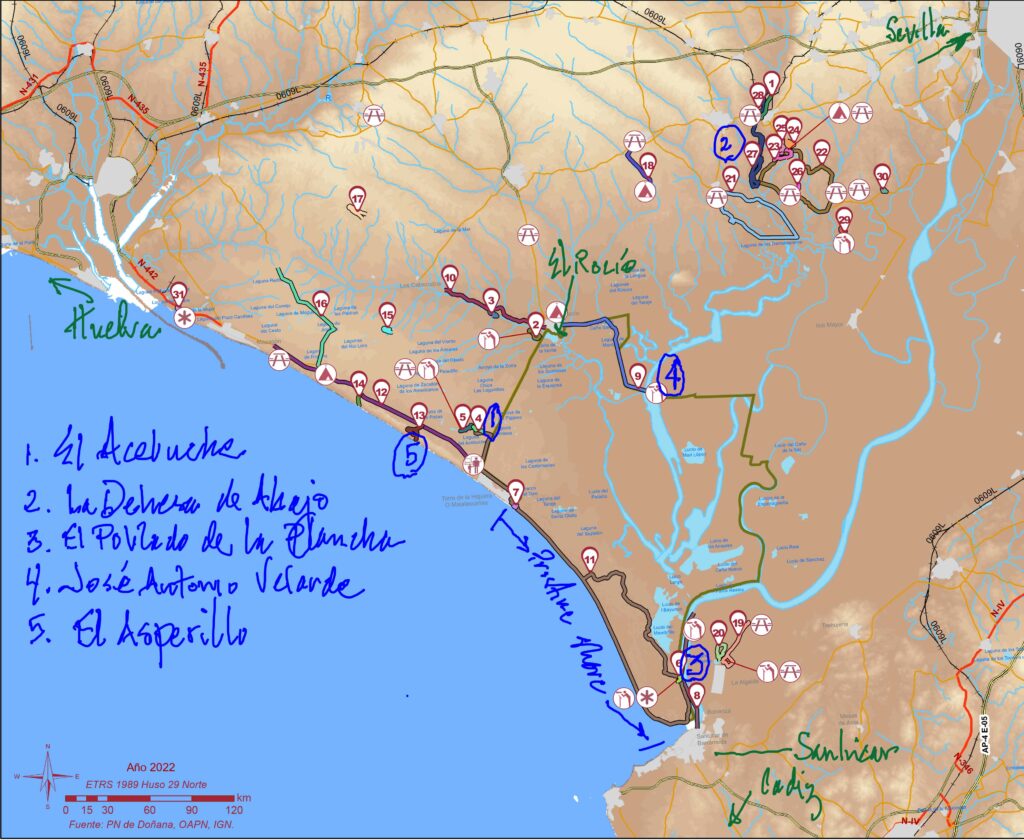

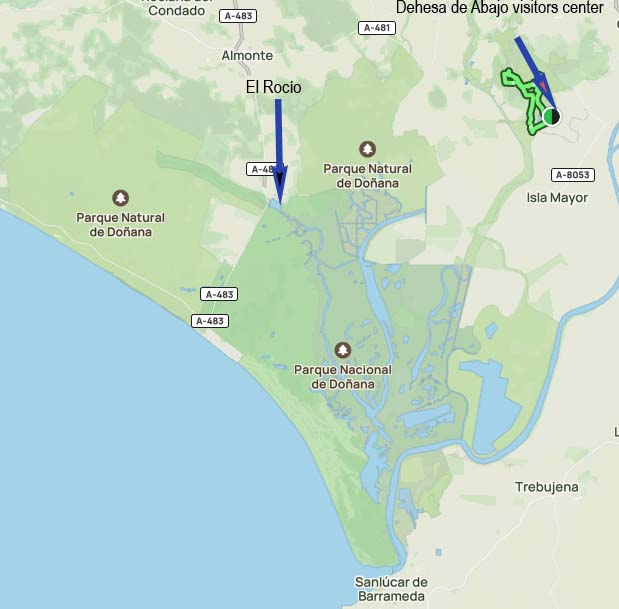

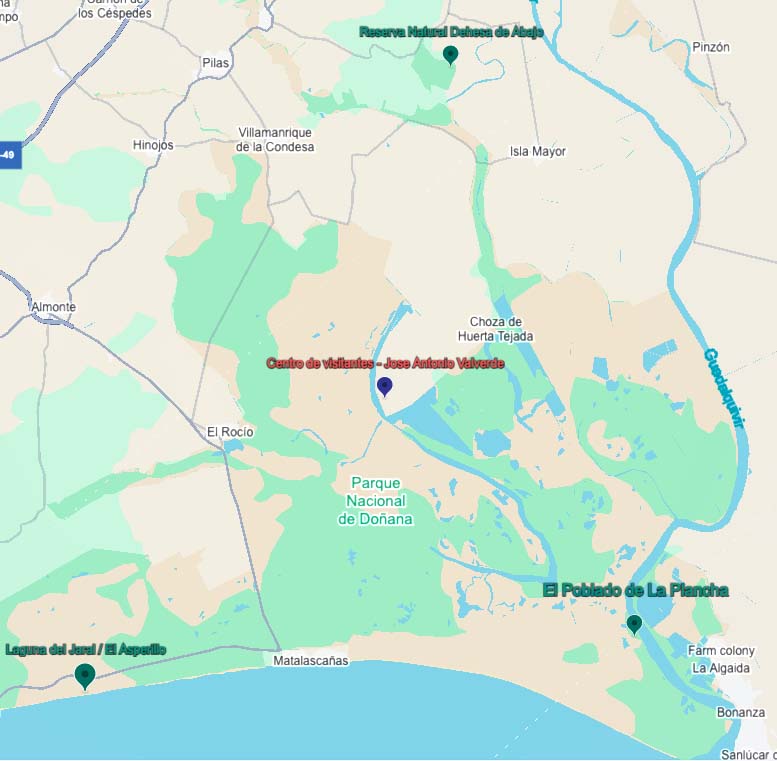

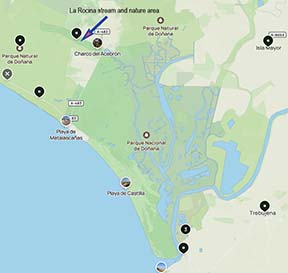

Secluded and elusive are terms that best capture my overall impressions of Spain’s Parque Nacional de Doñana, a nature preserve of unusually challenging access. There are the natural barriers that block entrance from the east and south, the Atlantic Ocean separating Doñana and Africa and the Guadalquivir River that sets the park off from Andalucía’s major cities (Cádiz, Málaga, Granada, etc.). The 550 km² National Park, which enjoys the highest level of environmental protection of any site in Spain, is surrounded to the north and west by 820 km² of a regulated Parque Natural, a buffer zone blending conservation and sustainable land use. Visitors may enter the Parque Natural via a network of small and often poorly maintained country roads. Access to the Parque Nacional is strictly limited to park authorities and official guided 4WD tours offering visitors glimpses of Doñana’s exceptional biodiversity: marshes, dunes, pine forests, lagoons, beaches, and scrubland. The park is home to over 300 species of birds, most prominently the Spanish imperial eagle, flamingoes, ibis, herons, spoonbills, storks, raptors, and a host of marsh waders. It is also home to a variety of mammals, most notably the resurgent Iberian lynx, (no longer on “endangered species” list), wild boar, and deer. Catching sight of any (certainly not all!) of these friends is a question of chance. With entry points to the park over an hour’s drive by car from Seville or Huelva (public transportation is complicated), one gets the sense that geography and regulations conspire in this tucked-away corner of peninsula in defense of a unique and fragile ecosystem, a fact that any visitor to the area should understand and appreciate in advance. I am now left with the sense that I probably failed to fully apprehend this in planning my trip.

For, like other trips I have planned recently, I seemed bent foolishly on the goal of “seeing it all.” This was due in part to this journey being yet another sort of torna atrás. My first visit to Doñana was a one-day blitz from Seville with a college friend and her older sister back in 1972. By the time we arrived, we were able to explore little on our very limited student budgets: a few spoonbills, some trees, a bit of the waterways and dusty trails. Nothing seemed compelling. Years later Augusta and I had a similar experience for similar reasons. Guided tours were out of the question. And yet I still believed that there had to be a hidden and magical core lying beyond the reach of my budget. I was meanwhile struck by lingering memories of chapter V, “Las Marismas,” in James Michener’s Iberia, a book that everyone seemed to think I had to read before studying in Madrid my senior year in college (1971). My skepticism about mass-marketed travel literature was nourished by the fact that, in the US, Michener was on every coffee-table traveler’ bookshelf. And I subsequently discovered that, along with the author of For Whom the Bell Tolls (“Hemingway ate here!”, “Hemingway slept here!”), Michener had garnered a reputation as yet another hero in Franco’s crusade to rope in foreign travelers… with their dollars. As to Michener’s marismas, I was ill-prepared to appreciate any discussion of how ecology, history and local culture intersect in a marshland habitat, nor had growing up near the beaches of California prepared me to appreciate the inherent and unparalleled beauty of such an environment.

Forty-five years of living near the Connecticut coastal wetlands and decades of teaching Federico García Lorca, along with many other life experiences, have turned those stunted sensitivities on their head, a fact that helps explain this particular torna atrás. A longstanding debt that was gnawing at me needed paying off. I needed to just had to go back to “get it,” to close another gap and to pay homage to one of mother nature’s uniquely resplendent sanctuaries. Most of all, I needed to simply commune in ways as I was less inclined or able to do when I was 20. I always knew that Doñana is special owing to its privileged location on the migratory highway birds follow from Africa to Europe and this year abundant rainfalls provided a golden opportunity. After years of drought, with the marshlands bone dry, the park is once again, at least for the time being, the aquatic paradise that Michener once evoked and that the locals recall.

And yet, as mentioned, owing to the various barriers and restrictions mentioned above, I learned most of all that expecting to experience Doñana as one would experiences other destinations is a challenging if not impossible proposition. Doñana, in the end, evades our knowing her. It is like a mirage, apprehensible only in its vague contours. In the end, I am left conjuring up a cubist-like collection of component parts arranged and rearranged at will. This is most likely my biggest take-away from this trip: that the beauty of Doñana lies precisely in the mystery that envelopes it, in the unseen as much as the seen, in the lingering desires it provokes. A case in point: Wednesday morning’s 5 hour 4WD tour of the park’s northern terrain began at 7am with a driver who moved deliberately through a wooded area so that his clients could experience the joy of seeing an Iberian lynx. Mr. Lynx is in high demand among Spanish visitory, but this morning he was a no-show. It is true that we learned a great deal about the animal’s habitat and behavior. And I take pride in my ability to envision this crafty feline in his habitat stalking his prey, or with a rabbit hanging from his jowls, just as our guide and posters in the visitors centers portray him.

So I look back and smile now at my futile attempt to define meticulously the coordinates of my search for an organic vision of the park rooted in a set of tangibles. Instead, I am left assembling a hodgepodge collection of the component parts of a collage, inviting others to think beyond and into the cracks in between, to appreciate the mysteries in which this site is unmistakable enshrouded.

Monday, May 5

Set off at 5pm from the Centro de Visitantes in our first 4WD tour, racing across the 30km virgin shoreline toward the mouth of the Guadalquivir River. Stunning views of a host of gulls and correlimos (sandpipers) set off against the background of a foamy, glistening low tide. Dunes to the left, with an array of grasses, junipers and sabinas. The junipers help to stabilize the dunes. The sabina (savin, a type of juniper), a precious wood for carpentry, hard owing in part to the effect of the salt in the water.

An occasional rancho or an abandoned cayuco or an isolated World War II bunker: the former, huts where fisherman take refuge, remnants of the area’s pre-park status; the second, make-shift vessels used by drug traffickers; the latter, testimonies to Franco’s allegiance to Hitler. Scattered blemishes on our collective consciousness and on an otherwise pristine coastline.

With Sanlúcar (civilization?) on the distant horrizons and correlimos (sandpipers) scampering about in the foreground…

headed off from the Guadalquivir headlands into Doñana’s interior.

Stopped to visit the Poblado de la Plancha, thatched dwellings where locals lived prior to the creation of the National Park in 1969.

Their livelihood derived from coal, forestry, hunting and fishing, apiculture and livestock farming. The indigenous vaca marismeña and the caballo marismeño –breeds of cattle and horses that the Spaniard took to the Americas; the former, ancestors to the longhorns– are in abundance.

Jumped back on our trusty 4×4, headed through woods out past a palace where Spain’s president stays when visiting the area, saw some boars (jabalíes) with her babies (rayones) and deer (still no sign of Mr. Lynx!),

crisscrossed more dunes and beaches before heading back to camp. Checked in late in our beautiful hotel along the marshes in El Rocío.

Tuesday, May 6

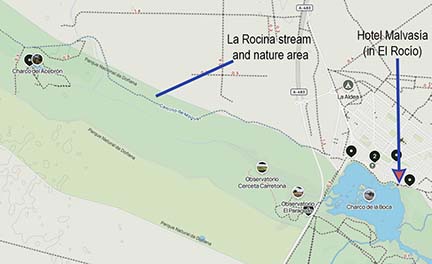

Our goal of discovering trails started with our hike around the Palacio del Acebrón and at the bird hides around the “Observatorios,” both in the La Rocina nature area.

La Rocina is a prime gateway to the park, with a small but fascinating ethnography museum. The site of elementary school teachers explaining local traditions to their young students renewed our confidence in the value of hands-on education in the field. The La Rocina stream is a vital tributary that irrigates Nacional Park, feeds the Rocío marshlands (la marisma del Rocío) and irrigates the northern part of the National Park.

Per the urging of the amiable park ranger at the Acebrón visitors center we headed out over 45 minutes of poorly paved roads from El Rocío to the Dehesa de Abajo. A remote outpost full of wildlife (especially birds), so remote in fact that the visitor center there is closed. Trails and hides are well maintained. Wetland landscape is remarkable. Felt like we stepped into a universe ruled by eagles, bee-eaters, cormorans, storks (one of the world’s largest population of nesting storks) and other creatures we love.

Seeing the sheer quantity of storks, the spectacle of the águila imperial español scavenge for food and the brilliant abejaruco take flight, not to mention silent splendor of the landscape, were ample reward for the bone-jostling pot-holed jaunt across the Parque Natural roadways.

Wednesday, May 7

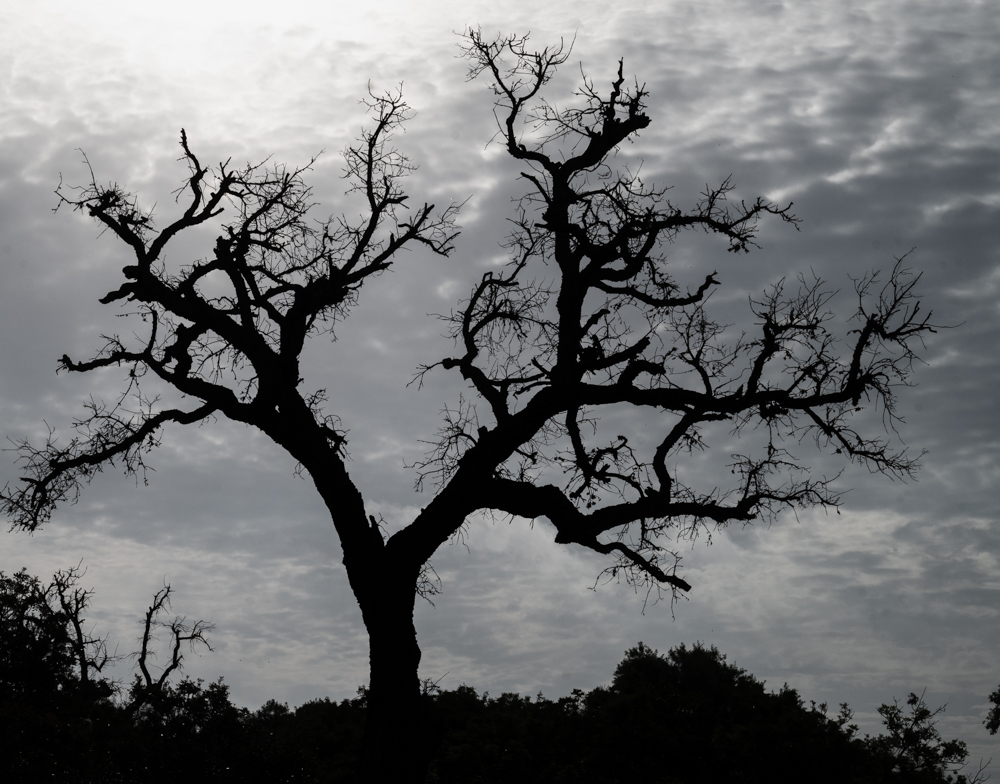

Departed El Rocío at 7am sharp accompanied by another couple and our guide, José, from Discovering Doñana, to explore the northern margins of the park. Traveled along dirt roads through fields, woods populated especially by alcornocales (‘cork oaks’), acebuches (wild olive trees) and lentisco (mastic tree), one of the more abundant shrubs that is native to this area.

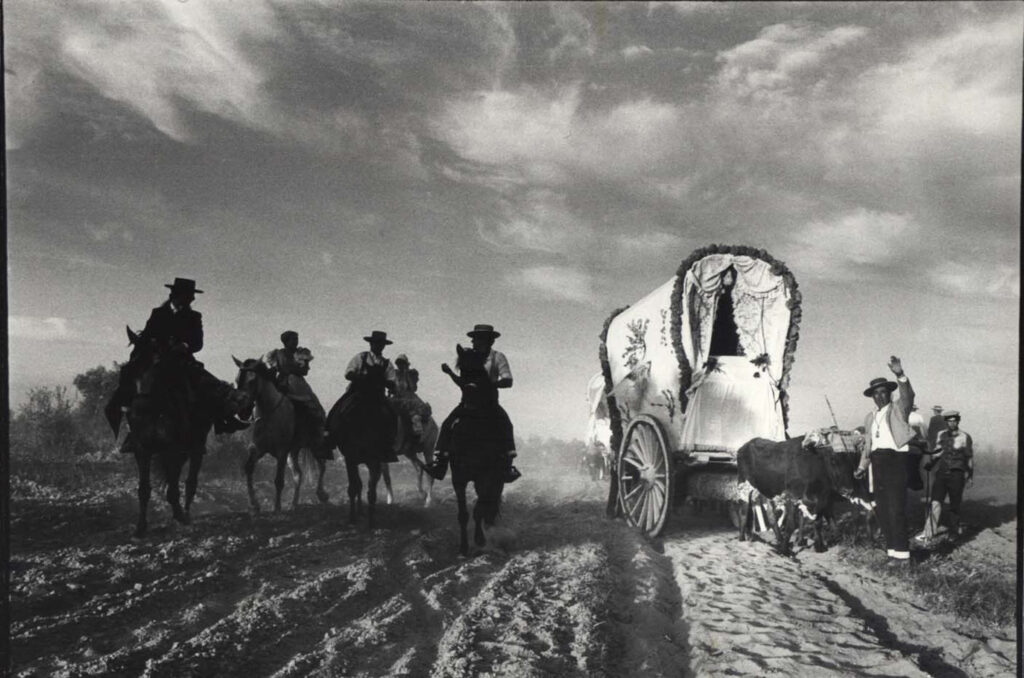

Followed at times pilgrimage routes used over the centuries by hermandades traveling by horse and cart for the annual romería, the fiesta de la Virgen del Rocío.

Notes on the romería de la Virgen del Rocío

Various casas de hermandades are maintained in the town of El Rocío by the religious brotherhoods that travel from their home towns to participate in the annual romería (the Pilgrimage to the Virgen of El Rocío). Sanlúcar de Barrameda’s hermandad was the first and is therefore the oldest (1660).

Back to nature

The José Antonio Velarde visitors center –getting there and being there– offers one of the most extraordinary birdwatching experiences imaginable. There is a sense here that one has penetrated into the deepest inner core of this mysterious region. Nature here seems to reign supreme.

Returning to our hotel after an exhilarating encounter with Doñana’s wildlife, we took off to hike the trails down past the Laguna del jaral to the Asperillo cliffs, overlooking a stunningly beautiful coastline.

Thursday, May 8

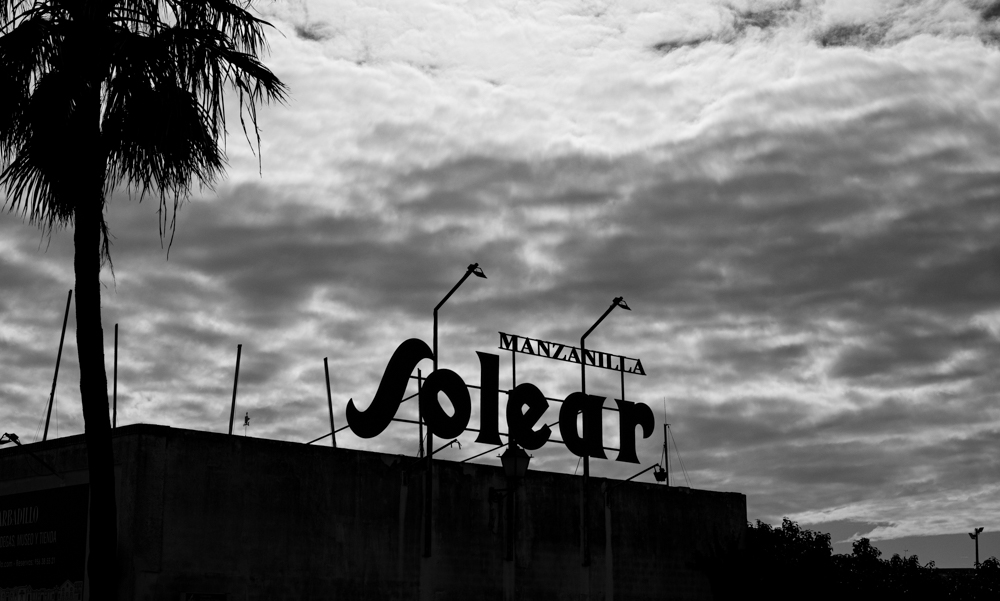

Reserved the 4pm visita fluvial expecting something unique about visiting Doñana by river. I also had that east-west-north-south thing in mind. This excursion was supposed to round things off with a tour of the “east”, contributing to that illusory organic understanding of Doñana. Turns out that the fluvial part was limited to our transfer across the Guadalquivir from Sanlúcar de Barrameda to the park, where we hopped on to another 4WD to tour areas visited on Monday. The repeat performance and the time spent in Sanlúcar prior to embarking was all nevertheless well worth it. Managed to plumb some of the grittier core of this quintessentially Andalusian city. Guides on the boat and on the 4×4 were especially informative and refined our understanding of Doñana. Also had front-row seats in the bus. Never too much of a good thing.

Seeing Doñana from Sanlúcar

Seeing Doñana from Sanlúcar An águila pescadora (Osprey)

An águila pescadora (Osprey) Currando…

Currando… Gambas, en el mercado de Sanlúcar

Gambas, en el mercado de Sanlúcar Andalucía’s famous sherries

Andalucía’s famous sherries

Friday, May 9

Awoke early to take one last hike around El Rocío. A surreal town that is somewhere beyond artificial. Has the feel of a Hollywood movie set.

And as a “set,” El Rocío prompts me to think about the how we experience the realities we encounter when we travel and how we represent them to ourselves, through remembrance or to others, via the stories we tell or the pictures we take. The dimension of that reality that needs addressing here are the deep emotions that Doñana sparked in us at key moments throughout the week, moments of sublime wonder.

We marveled, for instance, at discovering in a vast and open landscape all on our own –no other hikers, no guide to educate our eyes– the brilliant multicolored abejaruco (Bee-eater) resting on a post in an open field, gazing back at us as we gazed at him. It is hard to convey the thrill of discovering and then of capturing that fleeting moment as the bird took flight into the distance.

Solitude, silence and the vast beauty of the location are certainly key to the feelings we experienced at that moment, as they were when we hiked alone beyond the Laguna del Jaral out to the Asperillo cliffs, overlooking a nearly unimaginable panorama: the light shimmering over a foamy sea and casting shadows on the dunes, the cliffs, and in the crevices of a fine, richly variegated sandy shore.

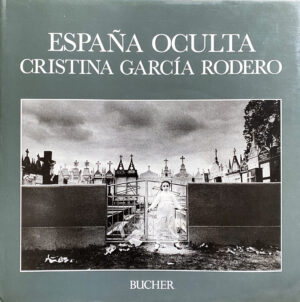

Waking up to the colloquium of the birds chattering busily outside our bedroom window in the Hotel Malvasía, located as it is on the shores of the Charco de la Boca (El Rocío’s marsh), or walking out the door of the hotel to confront the natural beauty of the water and vegetation, with horses, flamingoes and spoonbills communing across the water, with sparrows scurrying back and forth to their nests in the eaves of our hotel: all of this virtually alone, at 8am at least, with no sound other than the song of the birds to break the spell. Roaming the deserted streets of El Rocío our last morning brought all of this to mind, while we imagined echoes of the frenzied alegría of millions of pilgrims hastening along their now (for us) familiar romería trails, through the woods and across the marshlands, to convene in the casa of their hermandad, a reality so brilliantly captured by Cristina García Rodero.

In the silent and deserted streets, the casas sporting proudly with the names of their hometowns, sparked our sense of wonder, awe, a yearning to hear the now silent voices and songs of the people who have filled these streets over time.

An early morning fog descended upon the lagoon outside of our hotel our final morning in El Rocío to bid us adieu: a final reminder that all truths about Doñana are indeed encased within the mysteries of time, in the mist of our own illusions.

What an adventure. Thank you for sharing this wonderful part of Spain with us. Looking forward to more adventures.

So happy you appreciated this Letizia! More to come!

I never got to Doñana, and at this stage in life I knew I never would … Accepted

Then along came Mr. Bernardo Antonio González’s blog … and transported me to paradise found and I feel whole again. What a beautiful sanctuary, retreat and 6 senses renovation. Your narrative, photography and 6th sense are captivating. Thank you Thank you Thank you

You are so sweet to say this Vicky! Makes posting these reflections all the more meaningful.

What a lovely meditation on nature. Thank you for taking us along with you Antonio. I could feel the birds take flight and the bumps in the road. What a stunning place of beauty and how lucky the world is that it is being preserved. And, most of all, what a treat it was to see your name in my email!

Thank YOU Dorothie for coming along for the journey into nature.

Thank for sharing such beautiful sights from your trip. What an adventure for me as I sat on my armchair and traveled along with you. With your words I could smell the drifts from the sea and hear the chirping of the birds.. my Sister in law Maria shared your blog with me and what a delight. Buen Viaje Sr. Antonio. Will look forward to reading about more of your travels.. Hasta Luego

Thank you for reading me and for your thoughtful comments, Caroline! ¡Hasta siempre!