Viaggio in Sicilia / 12: 12 giugno – martedì

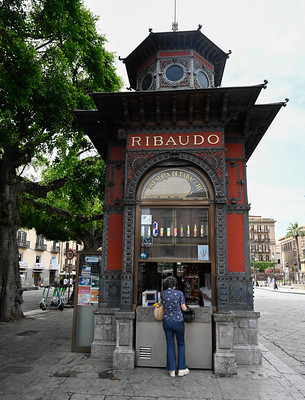

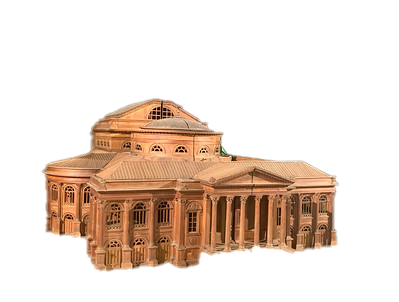

Today was billed as our Rick Steves Palermo walking tour day and, once again, RS did not disappoint! We began by heading down via Maqueda to our starting blocks, the serene Teatro Massimo seeming to slumber still in the early morning hours, while the city struggles to find its stride. Sitting opposite the stunning belle epoque theater, capped as it is with its commanding dome, surrounded by a chorus of blooming oleanders that cast color and shade around the piazza, occupying as the Massimo does its privileged spot –its throne– within the wide store-cafe lined open space: I allowed all of this to penetrate the senses while sipping my morning cappuccino. I was reminded once again of the unique value of traveling, of being there, of making the there then you’re here and now, and of the uniquely challenging struggle to stop, look, listen, smell, think, to capture it all the here and now with the imagination and, as much as possible, with a camera. Palermo on the morning of day two, in short, came alive, brilliantly, exhilaratingly!

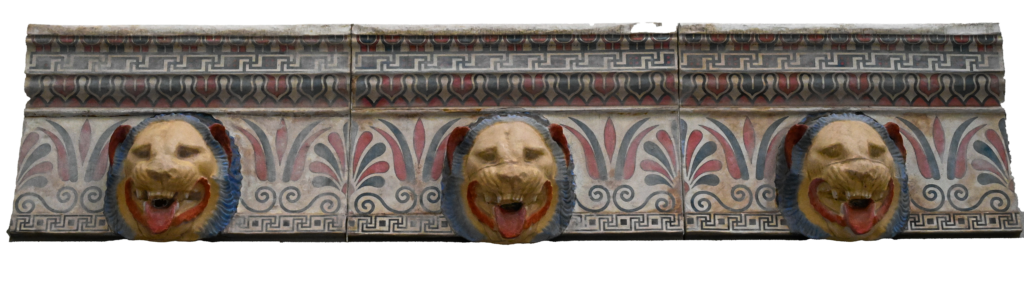

So… the RS walk sent us down the quaintly preened, polished and (at this hour) sleepy Bara all’Olivella past a series of old Palermo establishments –one being one of the many pupi places that we stumbled across during our stay here– and on to yet another archeological museum. Having seen Mozia’s, Agrigento’s, Siracusa’s and Aidone’s, we were wondering if a visit to the Museo Regionale Archeologico Antonio Salinas would really be… worth it? necessary? What would it add, in short, to our already bursting-at-the-seams imagination, chock full already of images of Persephones and Hermes? Well it was! Besides some uniquely beautiful sculptures and sarcophagi, the Museo Regionale has an unparalleled collection of material related to Selinunte (why isn’t this stuff there?), with decorative pieces from its temples, reconstructed façades, didactic displays and models and a superb 3D video that brings the 6th century BCE Greek city to life. A visit to the south coast site would be incomplete without visiting this museum, before or after.

From the museum we headed down the bustling and commercial via Roma, stopped to talk with the locals over coffee, gawk at the Fascist era imperial post office and step into San Domenico, with its imposing dimensions, exuberant baroque altars and oh-so-moving memorial to Sicily’s fallen hero, Giovanni Falcone, who was martyred by a bomb in his fight against the mob and is buried in this church… all this before leaving bourgeois Palermo behind and descending into the bowels of an increasingly seedy working class wannabe gentrified Vucciria neighborhood. The boisterous energy of a quarter clearly in flux was dazzling, even though we would have preferred seeing Palermitani shopping for fish and fruit rather than barkers wanting to feed it to foreigners. The charm still there but the context has changed. The ghosts of the 19th century Sicilian leoni –Paolo, Ignazio and Vincenzo Florio– seem to haunt the streets, the via dei Matterassai in particular, just off the extremely dilapidated Piazza del Garraffello, unreconstructed still after its World War II bombings. Throughout the neighborhood there are dilapidated façades of unreconstructed palaces, reminders of when the Calabrese Florio family arrived to set up their first putía and begin their century-long project of transforming the island’s economy and, to an extent, its society.

After making our way past a granita di limone at the Gelateria Lucchese, just off the Piazza San Domenico on the via Maccherronai (street names pay tribute to the trades and guilds that once thrived in this neighborhood) and then past the intense Piazza del Garraffello, we found ourselves in the petite, picturesque and somewhat secluded Piazza San Francesco, were good fortune brought us to the Oratorio di San Lorenzo.

It was in this compact gem of Sicilian baroque that we were truly able to commune with and appreciate the sumptuous style of the famous 17th century Sicilian sculptor, Giacomo Serpotta. This was my second encounter with this artist, the first being in Agrigento on my solo promenade around the old town. Maybe because I had become something of a convert to the high-flown style that predominates in Sicily or maybe because Palermo’s San Lorenzo truly surpasses Agrigento’s Santo Spirito in its magnitude, refinement and coherence, but whatever the reason we were enthralled by the beauty of this tiny chapel. The joy, once again, has to do with the being there, the seeing it without the hordes, more or less intact, just as it was originally created and in the space and place it was intended for. The sculptures, the tiles work, the representation of St. Lawrence on the grill, the fine copy of the stolen Caravaggio that presides over the alter, the place where the artist intended for it to live, and all of this in the oratorio that still thrives in the same neighborhood where the members of Palermo’s Rotary Club founded it in 1569: the dovetailing of image, architectural design, space and place. And then there was the social history dimension of the experience, shades of Arnold Hauser, the story that the sharp and amiable ticket vendor/guide shared with us with enthusiasm regarding the patrician community –the upper middle-class Rotarians– who set up their own prayer sites throughout the city, points of reference for bolstering civic engagement with spiritual reflection. The image of Saint Lawrence being martyred on a grill, captured in stucco on the wall opposite the main altar, is echoed in the tile pavement (just the grill). The relationship between this Franciscan Saint and Saint Francis are conveyed by the proximity to Church of Saint Francis (on the Piazza San Francesco, opposite the Antica Focacceria San Francesco) and, in the oratorio, iconographically. Scenes from the lives of the two saints are sculpted in stucco on the lateral walls. Caravaggio’s painting, of which a copy appears since the horrendous 1969 theft of the original, amplifies the symbolism of this corner of Palermo in its representation of the Nativity with Saint Francis and Saint Lawrence looking on from opposite sides.

Art appreciation tends to morph into the culinary, having both a common footing in the delectable. So we capped our morning walk and this moment of enchanted discovery with a snack in the Antica Focacceria di San Francesco, one of Palermo’s classics.

From San Francesco we followed RS’s plan out of the Vucciria and into La Kalsa in search of more urban baroque, charm, decay and history. At this point I began to get a much clearer idea of the four medieval quadrants –Palermo’s mandamenti– that rationalize urbanistic and socio-economic grid. The pieces would all fall perfectly into place our last morning, when complete our survey of the old-city neighborhoods with a stroll around the Capo and Ballarò market areas. But for now, the architectural and urbanistic hues of the city’s history, as they morphed from the 19th century bourgeois Capo to the gritty, rough-and-tumble timeless Vucciria and then on to the rather patrician and papal Kalsa, with its palaces, baroque churches and oratories, and its supreme monument to 19th century bourgeois prudery (hypocrisy?) –La fontana della Pretoria (aka “vergogna”)– this made our morning-to-afternoon Palermo walk entertaining and rewarding. The quattro canti intersection near our lodging took on new meaning and became our prime Palermo coordinate in so many ways.

It was interesting to note that on day 2 in Palermo the city began to seem less ragged. What decay we did encounter impacted us much less. It is also the case that the Ballarò market neighborhood raised the bar considerably in this regard. More on that tomorrow.

Palermo’s 19th century Teatro Massimo, Europe’s third largest opera house.

In anticipation of our evening engagement with George Gershwin’s Lady Be Good at the Teatro Massimo, we settled into siesta time at Baccavù’s heartfelt lodging on the via Teatro Biondi, put our feet up on the wall above the bed reaching to the ceiling, the skies, channeling celestial energies back to our street-worn brains and read. The Gershwin-Massimo surpassed our expectations! The theater-going experience was fascinating from start to finish, and involved watching the elegantly clad Palermitani flow into the elegantly adorned belle epoque coliseum blending with the smattering of European, American and Asian tourists. And yet, elegance in Sicily, at least when it concerns 18th and 19th haute culture venues, always beckons notions of formalities of fashion and custom whose decline come into sharper focus as one comes closer. We made sure not to touch the light fixtures and electric wires running along the short partition in front of our front-row gallery seats, just in case any of the wires was alive. We focused instead on the beautifully decorated and vented ceiling –a preindustrial and now highly sustainable air conditioning system– the red velvet curtains (looking so pristine from afar!) and sculpted wood throughout painted in glittering gold… as well as the superb performance by an American cast in this Teatro de la Zarzuela production. Somehow, the unique crosscurrents of elegant and passé, local and foreign all made for an exhilarating experience in Europe’s 3rd larges opera house, a building that I will no longer associate only with an American film noir about the Sicilian mafia.

We topped a superb day off with a delicious Sicilian dinner near our apartment, at the Vossia Cucina on Via Venezia, then slept with Gershwin’s melodies replaying over and over in my imagination.

Photo album available on Flickr at: https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjChynS