Beyond the Tajo

This is about traveling into a “beyond” that is defined by the course of a river. It concerns the Alentejo, a region in Portugal identified by its name as lying beyond the Tejo [‘táy-zhu’] river, the río Tajo in Spanish, the Tagus in English. Before the beyond, however, a few words about the river itself.

Many miles upstream from where this post takes me lies the monumental Toledo, a gem of a city defined by its Tajo in striking ways. The Tajo traces the outer banks of Toledo curving around it like a bow, caressing it as it take flight toward distant recondite pastures. The Tajo seems to burrow, as it flows implacably through the rocky ravines created over time for elevating the Roman, then Arab, then ancient imperial capital of the Visigoths and the capital of medieval philosophical debate involving Christians, Muslims and Jews, onto its regal perch. The 16th century painter Domenikos Theotokopoulos ‘El Greco’ captures Toledo’s sublime position in a cityscape that has become iconic. The contemporary Spanish film director Icíar Bollain draws on this iconicity in an emotive fable –Te doy mis ojos (Take My Eyes; 2003)– concerning the tragic downfall of two deeply wounded lovers, a movie that exalts not just Toledo’s unparalleled physical beauty but the lyrical tradition with which it is associated. Like the forlorn/star-crossed lovers in Garcilaso de la Vega’s 16th century Eclogues, shepherds who sing their “dulce lamentar” along the river’s banks, Pilar and Antonio “woefully lament” their tragedy as the resounding and luminous river flees by, oblivious to the tribulations of those who come there seeking solace. (Read more about this on my course website at: https://bit.ly/4jXE1pN; watch the clip from Bollain’s movie at: https://bit.ly/4m4W9QD)

Nothing remotely similar appears along the Tajo’s banks in its westward journey through Spain’s and Portugal’s Extremadura and Alentejo regions, nothing, that is, until the Tejo reaches Lisbon, where it experiences its dramatic finale in an expansive and formidable desembocadura into the Atlantic.

With the notable exception of Alcántara, a town of 1,500 inhabitants known for the celebrated Roman bridge that spans the river near Spain’s border with Portugal, there are no cities that approach the stature of Lisbon and Toledo nor fuse their charm with the river. One has the sense that once the Tajo abandons Toledo it disappears from our collective awareness, reappearing under Lisbon’s stately 25 of April bridge like Persephone reemerging in springtime. So different from rivers inscribed in the names of cities that grace the banks of the Thames (“Kingston-upon-Thames”), the Seine (“Vitry-sur-Seine”), or the Tauber (“Rothenburg ob der Tauber”), for instance. So different from the long train of cities that dot the banks of the Danube and that are featured in Claudio Magris’s essay Danubio, a reflection on the centuries-old cultural flow connecting ancient Greece and modern Germany. If there is any truth to the common belief that Spain and Portugal have positioned themselves stalwartly back-to-back, gazing away from each other over time, the Tajo’s/Tejo’s failure to serve as a Danube-like conduit seems to symbolize this breach.

Not only do these features represent the Tajo’s singularity but they help to explain the uniqueness of a quest beyond the threshold that the name “Alentejo” seems to suggest, a region that lies “allende” or “além de” (Spanish and Portuguese terms for ‘beyond’) the river Tejo. I have a certain fascination with locations named in relation to the rivers that they lie beyond: the Roman and Florentine “Trastevere” and “Oltrarno,” neighborhoods that, as their names imply, are on the other side of the Tiber and Arno. Such practices seem to convey, at the very least, a degree of alterity. They presuppose the existence of a privileged spot from whence one looks out toward a periphery, identifying it as just that: peripheral, “beyond,” “além de.” No surprise that the social fabric of these locations, in their origins at least, tended to be popular and not patrician. Yet any sense of the popular in Oltrarno or Trastevere has become shellacked by a Trip-advisor appeal to tourists seeking quaint 4-star taverns and inns. These once thoroughly peripheral neighborhoods lay claim today to an centrality that the shopkeepers, cobblers, smiths, street performers and wenches of old would hardly recognize, something that is obviously easier to achieve in medieval neighborhoods hitched on to urban centers of wealth and power. Not so with an immense rugged hinterland whose rough-and-tumble social fabric and equally rugged landscape are brilliantly portrayed by José Saramago in Raised from the Ground, a saga tracing generations of the class struggles of Alentejo’s indentured peasantry.

Needless to say, I too encounter this reality as a tourist… the eternal dilemma of how to represent the beyond without falling into demagoguery. In this case, I turn to some of the fleeting glimpses that two days in the Alentejo afforded me of the region’s rich complexity and raw beauty.

Before arriving at the Pousada in Arraiolos we stopped to visit the Cromeleque dos Almendres (the Chromelech of the Almendres), a prehistoric megalithic complex dating from the Neolithic age (maybe 7,000 years ago). The site is located deep within a cork oak forest near Évora and is one of many prehistoric sites that dot the local countryside. Whether this Chromelech hosted rituals or astronomical observation is lost in the fogs of time. Spanish Wikipedia claims this to be the “monumento más antiguo de Europa” (“Europe’s oldest monument”), a distinction that derives no doubt from pride more than from historical fact. But that pride, in and of itself, is clearly what the Portuguese feel for this forlorn site. We reached the ruins driving nearly a half hour along an unpaved, pot-holed dirt road, only to park and continue for another 20 minutes or so by foot along the muddy path, with other families and couples, before reaching the ruins. We passed a hand painted sign along the way –“Vergonha, Senhor Presidente”/”Shame on you, Mr. President”– as we marveled, along with others, at the enchanted forest of gnarly cork trees glistening under a late afternoon sun. Portugal lays claim to being the world’s number one producer of cork, an organic bottle stopper made from the bark of these trees that is unfortunately too often replaced today with plastic. The abundance of sugueiros (Spanish, alcornoques) in the Alentejo and in its neighboring Extremadura, in Spain, along with the almost eerie splendor of these majestic woods, contributes to the sense of difference that pervades this corner of the earth.

The high value that the Portuguese place on the cork as a cultural signifier, seems, in and of itself, equally significant.

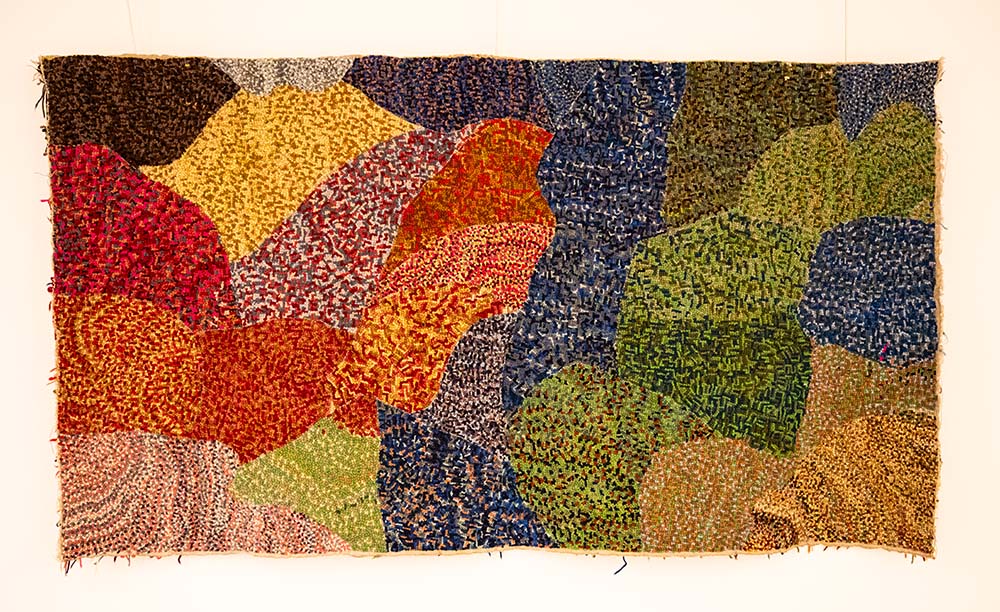

Corks in the Arraiolos Centro interpretativo

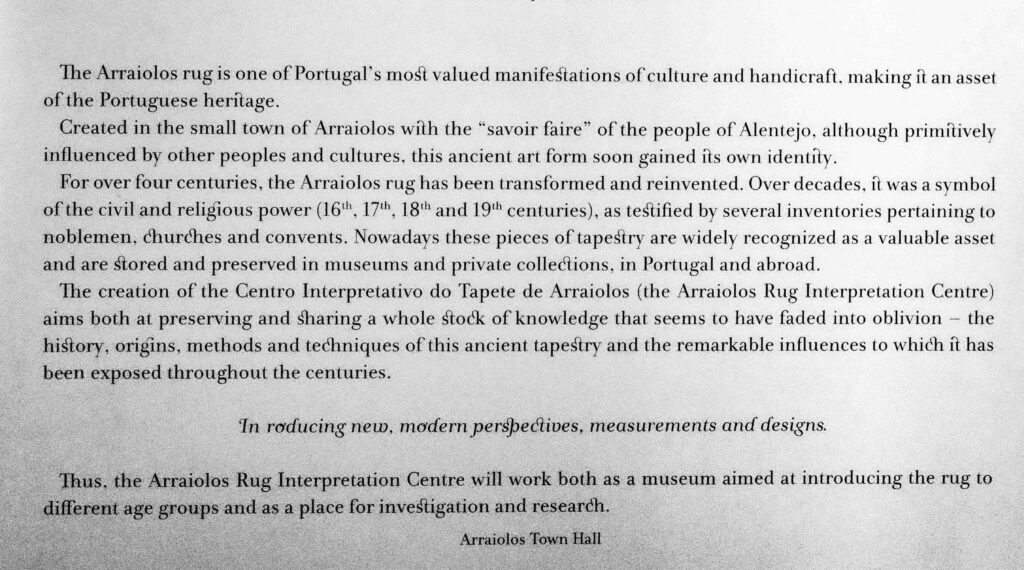

Other things that we experienced during our stay in the Alentejo made me think of the region in similar terms. Having “migas a alentejana” at a tavern in Arraiolos reminded me of the importance locals place on popular culinary traditions for setting themselves off as different. We learned about the craft of carpet weaving that has thrived in Arraiolos over the centuries. According to the local museum, weaving was introduced by the Arabs and drove the many private enterprises that used to fill the city, until modern economic trends forced closures. The proximity of the museum to abandoned buildings and tourist shops selling samples seems to speak to our times.

An Arraiolos carpet in the Centro interpretativo

An Arraiolos carpet in the Centro interpretativo Arraiolos’s main square, with a replica of a carpet in the pavement

Arraiolos’s main square, with a replica of a carpet in the pavement One of the traditional carpet workshops, now closed

One of the traditional carpet workshops, now closed

An Arraiolos carpet from the 18th century, in Lisbon’s Museu de Artes Decorativas

An Arraiolos carpet from the 18th century, in Lisbon’s Museu de Artes Decorativas Arraiolos’s Centro Interpretativo

Arraiolos’s Centro Interpretativo

Lastly, the Arraiolos fortress perched high above the city. Originally Arabic, the fortress today is a remnant of when the Portuguese, having won their independence from Spain in 1640, had to buttress themselves against their arch-enemy to the east while turning their gaze to the riches beyond the Atlantic. In some ways this seems ironic. Across the border is Spain’s Extremadura, a place whose name –a “hard” (read: inhospitable) “extreme” (read: margin)– conveys the sense that this region is a backcountry to Madrid just as the Alentejo is to Lisbon. Alentejo and Extremadura: two regions conjoined by more than what history and national boundaries might suggest.

They are also two regions, it must be said, that place great value on the quality of their migas.

These reflections would be incomplete without reference to our experience with Alentejan wine, a product that has enhanced this region’s global status. We visited the Herdade de Colheiros near the town of Igrejinha, a family estate that, as their web site indicates, is much more than just a winery. It is a multifaceted enterprise that promotes an eco-friendly development of the land and that organizes the various parts of the estate to promote a natural synergy. The elements include olive groves, pine forests, oak forests (“Montados”) and wetlands. The Herdade raises sheep for wool, bees for honey and pollination, while it cordons off areas as wildlife preserves (for deer, boar, the Iberian lynx, and so forth). We saw much of this from our jeep, during our guided tour of the grounds, before proceeding to a tasting room, a modern structure of stunning architecture set high up on a hill. In a room encased in glass and surrounded by nature, our knowledgeable guide offered us delicate whites and rosés, and the deeply rich, ruby-red tintos of the Tapada dos Coelheiros label for which the estate is best known. All in all, our experience at the Herdade rekindled our faith in private enterprise’s ability to contribute to our well-being and the well-being of our planetary homeland.

Returning to Madrid, I pick up once again Daniel Mason’s North Woods, a myth-based novel concerning the history of a hinterland not far from where we live in Connecticut. The protagonist in this section is a painter whose transcendent penetration into the thick woods and orchards of western Massachusetts reminds me of my walk, camera in hand, through Alentejo’s cork oak forests:

“Off to the river, now roaring with melt. Easel on my back—no more sketching just in service of a later canvas: this would mean running the world through the sieve of my perception, and I wish to paint what is. Scramble over boulder until I find my spot and then try to paint, an effort, for the theatre is such that one just wants to sit and look. Yes, ‘threshold’ was the right word—I leave the world and cross into this enchanted place. Woods, from the Old English wode…also meaning ‘mad.’”

One final word. Nowhere in the vicinty of Évora, Arraiolos or of any of the sites we visited is the Tejo river visible. It remains far off in the distant, as an idea, an imaginary marker of difference that is itself no doubt foreign to the Alentejanos.

Loved your story. Looking forward to more adventures.

Thank you Letizia!